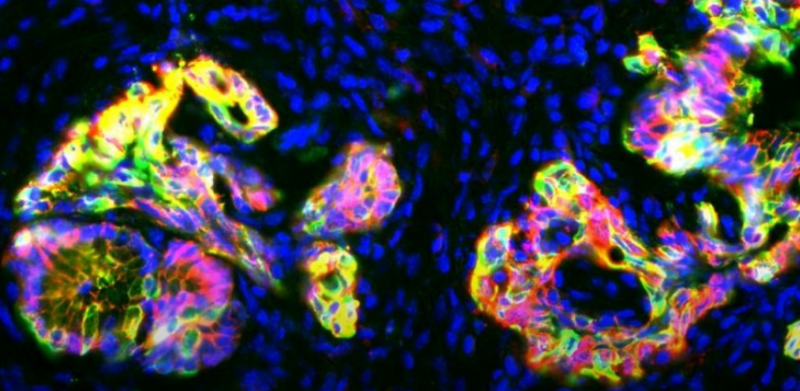

According to a new study by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Cancer cells produce small amounts of their own form of collagen, creating a unique extracellular matrix that affects the tumour microbiome and protects against immune responses, This abnormal collagen structure is fundamentally different from normal collagen made in the human body, providing a highly specific target for therapeutic strategies.

The study was published in Cancer Cell, which was in addition to previously published findings from the laboratory of Raghu Kalluri, M.D., PhD, chair of Cancer Biology and director of operations for the James P. Allison Institute, to bring a new understanding of the unique roles of collagen made by fibroblasts and by cancer cells.

Senior Author of the Study Kalluri said, "Cancer cells make atypical collagen to create their own protective extracellular matrix that helps their proliferation and their ability to survive and repel T cells. It also changes the microbiome in a way that helps them thrive," They further added, "Uncovering and understanding this unique adaptation can help us target more specific treatments to combat these effects."

In order to investigate the real-world effects of this observation, the researchers created knockout mouse models of pancreatic cancer with COL1a1 deleted only in cancer cells. Loss of this cancer-specific homotrimer reduced cancer cell proliferation and reprogrammed the tumour microbiome. This led to lower immunosuppression, which was associated with increased T cell infiltration and elimination of cancer cells.

Additionally, these knockout mice responded more favourably to anti-PD1 immunotherapy, suggesting that targeting this cancer-specific collagen could help boost the anti-tumour immune response.

"This discovery illustrates the importance of mouse models, as it was only when we noticed a difference in their survival that we found this abnormal collagen variant existed and was produced specifically by the cancer cells," Kalluri said. "Because it is generated in such small amounts relative to normal collagen, the homotrimer would have otherwise gone undetected without specific tools to differentiate them."

The study also found that the abnormal collagen upregulates signal pathways associated with cancer cell proliferation by binding to a surface protein called integrin α3. Indeed, suppressing integrin α3 in vivo increased T cell infiltration and prolonged survival, highlighting this interaction as a very specific target for potential therapeutic strategies.

"No other cell in the normal human body makes this unique collagen, so it offers tremendous potential for the development of highly specific therapies that may improve patient responses to treatment," Kalluri said. "On many levels, this is a fundamental discovery and a prime example of how basic science unravels important findings that could later benefit our patients."

While the current study looked specifically at pancreatic cancer, Kalluri noted that collagen homotrimers also are seen in other cancer types, including lung and colon cancers, signifying a possible unifying principle with broad implications for cancer treatment.

Higher voice pitch lets female faces appear younger: Study

Strokes linked to Depression: Study

Immunotherapy might help to Improve Lung Cancer Treatment: Study