Shaam Singh was born in 1790, at the dawning of the independent Sarkar Khalsa. His father, Nihaal Singh had originally served under the Bhangi Misl before joining Maharaja Ranjit Singh

Shaam Singh received a high degree of education, studying Gurmukhi, Persian, and English before being granted command over 5000 troops. He participated in numerous Sikh State (Sarkar Khalsa) victories, including the battles of Attock, Multan, and Peshawar as well as the conquest of Kashmir.

Also Read: Akali Baba Binod Singh Nihang : Changed Course of Sikh History

A meeting between the Maharaja and the British under Lord William Bentick was arranged by Shaam Singh, who eventually rose to the position of one of Ranjit Singh's most trusted advisors, in 1831 at Ropar. When he wed his daughter to Maharaja Ranjit Singh's son, Nau Nihal Singh, his influence was further increased.

Shaam Singh regarded as a loyalist, was placed in the most remote areas of the Sikh State after Ranjit Singh's death while the Dogra brothers prepared their plans to usurp the throne. While the Dogras were killing their way to power in Panjab, Shaam Singh was finishing expeditions on the fringe of the Sarkar Khalsa. Shaam Singh was persuaded to go back to the plains of Panjab by the passing of Nau Nihaal Singh, his son-in-law and Ranjit Singh's grandson. After fighting and executing Hira Dogra, Shaam Singh conducted a campaign against the Dogra family, forcing them from Panjab. The Dogra family, who were working for the British government, wanted to introduce the British into Panjab to help them take the crown. Shaam Singh persuaded the Sikhs to take care of their own house before fighting foreign adversaries and looked to lead a decisive campaign against Gulab Dogra. Shaam Singh was aware of the Sikh weakness against British guns.

Also Read: Rani Sada Kaur: A Sikh Leader

Maharani Jindan, the ruler of the Sarkar Khalsa at the time, had purchased the Khalsa Army to uphold her reign by promising to give the soldiery enormous sums of money. The troops started to turn against her once this money failed to materialize. She threw the Khalsa Army onto the British, who had already started stirring up Sikhs at the border, out of panic. The British just needed this and the Dogras' assurances of support to enter Panjab. Lal Singh and Tej Singh were picked by Maharani Jindan to command the Khalsa Army. Unbeknownst to Maharani Jindan, the Dogra family had risen to the top positions within the Sarkar Khalsa, and records from the British Empire reveal that both Sikh commanders, Lal Singh and Tej Singh, were also paid by the British.

Also Read: Jassa Singh Ahluwalia: Spiritual Leader

The Battle of Mudki unearthed the first treacherous commander. With victory within Sikh sights, Tej Singh inexplicably withdrew from the field, telling his soldiers that he felt the British were feigning a maneuver. At the Battle of Ferozeshah, the Sikhs were again within sight of destroying the East India Company, but again Lal Singh without any reason fled the battlefield and the reinforcements by Tej Singh failed to arrive. With Sikh power effectively curtailed by the commanders' treachery the Sikh state had fallen in all but name, however, the Sikh Army continued the fight at Aliwal, despite having already lost a considerable number of men and guns.

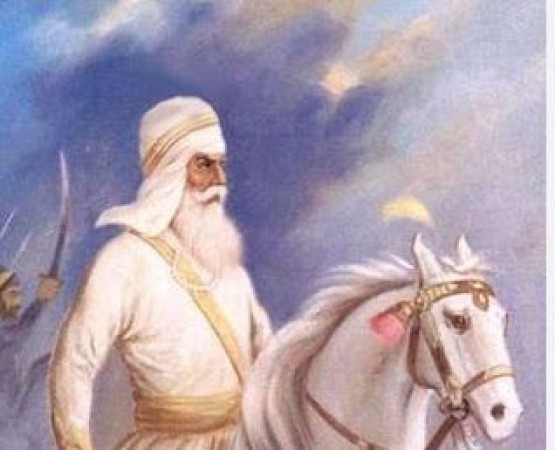

Disgusted, Shaam Singh, who was then 60 years old, took part in the Battle of Sabraon on February 10, 1846, the last engagement of the First Anglo-Sikh War. In keeping with his pledge to the British to trap the Sikhs, Tej Singh again departed the battle early and destroyed a bridge behind him. Up until Shaam Singh approached the scene, clad in white robes, a white dastaar, and riding a white horse, the leaderless Sikhs were being comfortably routed.

Also Read: Chardi Kala: An Ascending Energy

The Sikhs, who had been left in a demoralized state, were stirred into fighting once more as he rode from column to column urging his soldiers to fight to the bitter end. Shaam Singh galloped into the heart of the conflict and made a valiant last stand that became as well-known as any made before him. Although attacked on either side by horses and battalions of foot, no Sikh offered to capitulate and none requested for the quarter. Instead, many surged forward to meet certain death by contending with a crowd, according to the British aid-de-camp to the governor-general who was present during the conflict. The winners saw the unflappable bravery of the defeated with stoic astonishment.