CGTN's First Voice provides instant commentary on breaking stories. The daily column clarifies emerging issues and better defines the news agenda, offering a Chinese perspective on the latest global events.

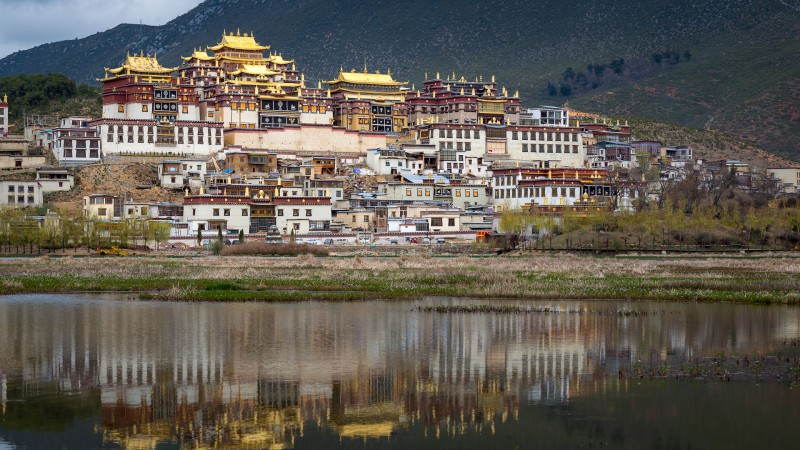

In the minds of many Westerners, Tibet is one of the last wild places on Earth, with a vibrant pure form of religion that links humanity back to its ancient roots and a pristine landscape unchanged from prehistoric times.

In short, it is Shangri-La and a counterpoint to the complex, often stressful lives of the modern era. From this perspective, it is easy to see why many good-hearted Westerners have been alarmed by the growth of cities, construction of roads and the appearance of a dwindling ancient way of life in the 70 years since it was peacefully liberated by China.

But, by mourning for that "Tibet," these Westerners are also mourning for the simpler times they image they themselves have lost. However, the reality of life in Tibet and the changes that have taken place since the demise of Tibet's theocratic feudal serfdom is quite different.

On May 21, China's State Council Information Office issued a white paper on the peaceful liberation of Tibet and its development over the past seven decades, which offers some context for people who mourn the loss of a Shangri-La that never existed. In old Tibet, there was a rigid hierarchy, with people divided into three classes by blood and position. The upper class, just 5 percent of the population, owned almost all of the land, pastures, forests, mountains, rivers and flood plains, and most of the livestock.

Before the democratic reforms in 1959, there were a mere 197 hereditary aristocratic families, and the few top families each possessed dozens of manors and thousands of hectares of land. The family of the current Dalai Lama owned 27 manors, 30 pastures, 4.8 tons of gold, 2.8 million tons of silver, and more than 6,000 serfs. Serfs and slaves, who accounted for 95 percent of the population, had no freedom or way to make a living. They were exploited through corvée labor, taxes, and high-interest loans and struggled to eke out survival. They had no access to schools other than lamaseries or hospitals — because there were none. They could not own property.

An Italian village that was once under water has now reappeared dramatically

INDIA’S BEST PLACES FOR WATER SPORTS

Portugal declares itself safe to travel with minimum restrictions